Measurements Gone Wrong: What Real Failures Teach Us About Measurement Risk

Most measurement failures don’t start with a dramatic mistake. They start with something ordinary: a unit that isn’t clearly defined, a calibration performed under the wrong conditions, a process step skipped because “it’s always been fine,” or a requirement that no one can clearly explain. Then a decision gets made, accept, reject, proceed, launch, and the consequences show up downstream.

That “downstream” point is the key. Measurements exist to support decisions, and every decision follows the same path: Measurement → Decision → Consequence [A]. The measurement rarely causes damage by itself. The damage happens when a bad measurement (or a misunderstood one) becomes a confident decision.

A practical way to think about measurement reliability is as a three-legged stool:

- Requirements (what you need to know, and why)

- Equipment (what you use to measure)

- Process (how you perform and control the measurement)

If any leg is weak, the “decision” you’re sitting on becomes unstable—no matter how good the math looks. Your presentation frames this as: know the right requirements, choose the right equipment, and have the right processes [A].

What follows are real-world examples—each one a reminder that measurement risk is not theoretical. It’s operational, financial, and sometimes fatal.

1) The Vasa — When “an inch” isn’t an inch

In 1628, the Swedish warship Vasa sank less than a mile into its maiden voyage. One contributor discussed in modern reporting is that shipbuilders used rulers based on different measurement systems, creating inconsistent construction and instability [1].

What failed: requirements (common measurement system) and process (standardization/verification).

Lesson: If definitions aren’t shared and enforced, the measurement system can’t save the decision.

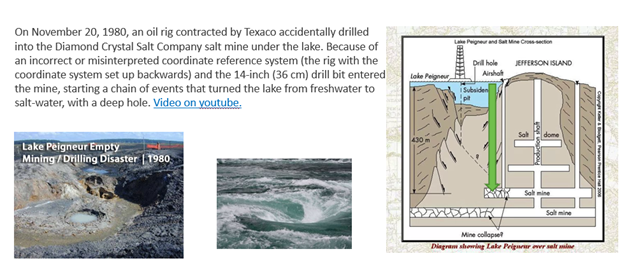

2) Lake Peigneur — A positioning/reference failure that cascaded

In 1980 at Lake Peigneur (Louisiana), a drilling operation punctured a salt mine beneath the lake, triggering flooding and a dramatic sinkhole/whirlpool event. Accounts emphasize an incorrect location/reference understanding that led to the drill intersecting the mine [2].

What failed: requirements (correct location definition) and process (independent verification).

Lesson: Some “measurement” failures are really reference-frame failures—coordinates, maps, assumptions, and verification steps.

3) Hyatt Regency Walkways — Verification missed, consequences were immediate

On July 17, 1981, the Hyatt Regency skywalks collapsed in Kansas City, killing 114 and injuring hundreds. A key factor documented in major investigations is that a design/change detail dramatically altered load paths, and the connection failed catastrophically [3][4].

What failed: process (engineering change control and verification) and requirements (ensuring design meets load/code intent).

Lesson: High-consequence systems require high-discipline verification—especially when changes alter the risk landscape.

4) B-2 crash (Guam, 2008) — “Calibration done right” under the wrong conditions

A B-2 accident investigation found that moisture in air data components during air data calibration distorted sensor output, contributing to erroneous flight control inputs and loss of the aircraft during takeoff [5].

What failed: equipment/environment controls and process controls (detecting/mitigating moisture effects during calibration).

Lesson: Calibration isn’t a magic reset button. A calibration performed without controlling critical conditions can create false confidence.

5) CoxHealth/BrainLAB — Wrong tool, right intent, years of undetected harm

In Springfield, Missouri, a stereotactic radiation therapy system delivered incorrect doses for years. Reporting describes systematic error linked to calibration/measurement method problems and weak independent verification [6][7].

What failed: equipment selection (appropriate measurement method/device) and process (independent verification and detection controls).

Lesson: Repeatability is not correctness. A process can be stable and consistently wrong if the setup is wrong.

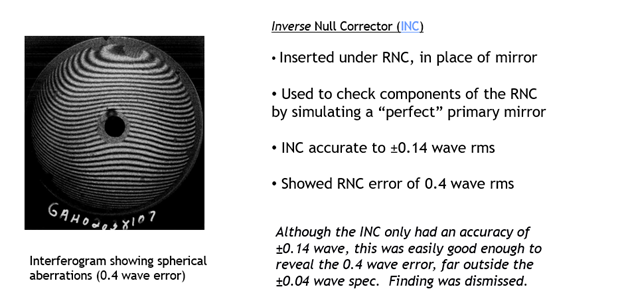

6) Hubble Space Telescope — Measurement warnings were good enough… and still ignored

The Hubble launched with a mirror figure error that severely degraded optical performance. Investigations trace the issue to test equipment and process/decision failures that allowed contradictory evidence to be dismissed before launch [8][9][10].

What failed: process (cross-checking, criteria, escalation) and decision discipline when results contradict expectations.

Lesson: Sometimes the failure isn’t measurement capability—it’s organizational decision risk: what happens when measurement evidence conflicts with schedule or assumptions?

7) BP Texas City — When signals don’t drive decisions

The 2005 BP Texas City refinery explosion and fire killed 15 and injured 180+. The U.S. Chemical Safety Board documented major process safety management breakdowns, including weaknesses in instrumentation awareness, safeguards, and decision-making under abnormal conditions [11][12].

What failed: process and requirements—what triggers action, how warnings are handled, and how risk is governed.

Lesson: In high-consequence environments, measurement only protects you if the organization has reliable decision pathways that respond to it.

Pulling it together: measurement risk is likelihood and consequence

These cases all show the same pattern: the catastrophe is rarely “the measurement.” It’s the decision made using a weak system—unclear requirements, incapable/compromised equipment, or poor processes—and the downstream consequences that follow.

Risk management is not about obsessing over one metric. It’s about making deliberate choices:

- How likely is a wrong decision?

- What happens if we’re wrong?

- Who bears the consequence?

The practical takeaway from every example above: reduce risk by strengthening the whole system—requirements, equipment, and process—not by relying on a single technique or assuming “the number” is enough.

Engineering failure is measured in two ways:

- Human death toll

- Materials lost.

Even when the technical concepts are clear, the real vulnerability often isn’t math—it’s mindset. When processes seem to work, it’s easy to treat the current approach as “safe enough,” especially when no major failures have surfaced. But decision rules that default to simple acceptance can quietly erode safety margins over time, normalizing higher risk without anyone explicitly choosing it. That’s how uncertainty becomes invisible: not through bad intent, but through routine.

"Failures appear to be inevitable in the wake of prolonged success, which encourages lower margins of safety. Engineers and the companies who employ them tend to get complacent when things are good; they worry less and may not take the right preventative actions." - Heny Petroski

Petroski's claim about complacency might merely describe human nature, or it might point to the old but well-known motto, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." After presenting the information above, the question for you is what are you going to do in your organization to help make the world a safer place.

References

[A] Zumbrun, H. “Measurements Gone Wrong” (webinar, presentation), Morehouse Instrument Company, June 6, 2024.

[1] GBH (WGBH). “New Clues Emerge in Centuries-Old Swedish Shipwreck (Vasa).”

https://www.wgbh.org/news/national/2011-03-01/new-clues-emerge-in-centuries-old-swedish-shipwreck

[2] 64 Parishes (Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities). “Lake Peigneur Drilling Accident.”

https://64parishes.org/entry/lake-peigneur-drilling-accident

[3] NIST (NBSIR 82-2465A). “Investigation of the Kansas City Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse.”

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/IR/nbsir82-2465A.pdf

[4] NIST Publication Landing Page (Hyatt Regency Walkways Collapse).

[5] U.S. Air Force. “B-2 accident report released” (moisture in PTUs during air data calibration).

https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/123360/b-2-accident-report-released/

[6] Radiology Business. “76 patients over-radiated at Missouri hospital” (CoxHealth/BrainLAB reporting).

[7] HealthLeaders Media. “Radiation Errors Reported at Missouri [Hospital]” (additional coverage).

https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/strategy/radiation-errors-reported-missouri

[8] NASA Science. “Hubble’s Mirror Flaw.”

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/hubble/observatory/design/optics/hubbles-mirror-flaw/

[9] ESA/Hubble. “The Aberration Problem.”

https://esahubble.org/about/history/aberration_problem/

[10] NASA Technical Reports Server. “Hubble Space Telescope Optical Systems Board of Investigation Report.”

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19920008654/downloads/19920008654.pdf?attachment=true

[11] U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB). “BP America Refinery Explosion” (case page).

https://www.csb.gov/bp-america-refinery-explosion/

[12] CSB. “Final Investigation Report PDF” (BP Texas City Refinery Explosion and Fire).

https://www.csb.gov/file.aspx?DocumentId=274

About Morehouse

We believe in changing how people think about Force and Torque calibration in everything we do, including discussions on measurements gone wrong.

This includes setting expectations and challenging the "just calibrate it" mentality by educating our customers on what matters and what may cause significant errors.

We focus on reducing these errors and making our products simple and user-friendly.

This means your instruments will pass calibration more often and produce more precise measurements, giving you the confidence to focus on your business.

Companies around the globe rely on Morehouse for accuracy and speed.

Our measurement uncertainties are 10-50 times lower than the competition, providing you with more accuracy and precision in force measurement.

We turn around your equipment in 7-10 business days so you can return to work quickly and save money.

When you choose Morehouse, you're not just paying for a calibration service or a load cell.

You're investing in peace of mind, knowing your equipment is calibrated accurately and on time.

Through Great People, Great Leaders, and Great Equipment, we empower organizations to make Better Measurements that enhance quality, reduce risk, and drive innovation.

With over a century of experience, we're committed to raising industry standards, fostering collaboration, helping with understanding risk, and delivering exceptional calibration solutions that build a safer, more accurate future.

Contact Morehouse at info@mhforce.com to learn more about our calibration services and load cell products.

Email us if you ever want to chat or have questions about a blog.

We love talking about this stuff. We have many more topics other than measurements gone wrong.

Our YouTube channel has videos on various force and torque calibration topics here.

# Measurements Gone Wrong